Regrets? I have many, but one is a real whopper

How I changed directions on an important social issue as I got older

Dear Muggles and Mugglettes:

Ah, regrets. I try to minimize them, but there are plenty, and they keep piling up.

Regrets were easier to ignore in my haughty younger years, but now that age is humbling me (I'll be 69 in July), I hear them flapping around like bats in the night, usually in the “hour of the wolf,” that is, 3 AM.

“Whoa,” I say to myself, half asleep and filled with dread. “I definitely should not have done THAT.”

Regrets aplenty.

My first hope is that there is no vengeful god and that I won’t have to answer for my crimes. If I do, I will spend several eons in purgatory trying, in vain, to tear the tops off those little packages of catsup they hand out at McDonalds, all while listening to Leslie Gore sing “It’s My Party and I’ll Cry If I Want To,” over and over, which is my version of hell.

My second hope is that God just won’t remember. It’s a happy thought.

My Shameful Whopper

I’m too embarrassed to mention most of my mistakes here in public, but there is one to which I must confess: Laughing at Ebonics. For those who need a refresher on this term, here is the definition from Wikipedia:

Ebonics (a portmanteau of the words “ebony” and “phonics”) is a term created in 1973 by a group of black scholars who disapproved of the negative terms being used to describe their type of language. The term Ebonics has primarily been used to refer to the sociolects of African-American English, which typically are distinctively different from Standard American English.

It was fair sport in my years as a young Christian for my pious friends and me to skewer all things liberal, and Ebonics was a pheasant plucked and ready for our fire of moral indignity.

“Why don't they just learn to speak normal English?” we said with a sniff, as if there is such a thing as “normal” English.

Ugh. That regret is a whopper. I’m cringing about it now.

Today, when I return to my home state of Virginia, one of the warmest sounds I hear is Ebonics. That familiar black accent is a rarity outside of the United States. It is, for me, the comforting sound of home.

Later in life, I had a change of heart about Ebonics. In 2014, I wrote the following true story about a bike ride I took one frosty day in November just after Thanksgiving. The story is called “Riding with Sly,” and it’s what I saw that day... from the balcony.

From the Balcony

I took a break from pretending to work today for a wintry bicycle ride. The air is cold, but the sun is bright, and the roads are dry—a good day for cycling.

A few miles into my ride, another cyclist, a man, pulled up beside me, and we began to talk.

“I’m trying to work off THREE PIECES of cheesecake,” he told me.

“New York style? The creamy kind?” I asked, as we peddled along together.

“Oh yeah,” he said. “Made by my goddaughter.”

And so it went, with casual talk about the merits of deep-fried turkey versus baked, and of smoked salmon, and of pumpkin pie crisp served with real whipped cream. Just two strangers talking the same language, of food and family, as the bucolic Virginia countryside, with its flaxen fields and weathered gray houses drenched in the afternoon sun, slid by our silent metal horses.

My gears slipped unexpectedly on a shift.

“I can fix that,” he said, and with a few expert twists of a barrel knob he did, and I was back on the road, my bike shifting as smooth as I imagined his goddaughter’s cheesecake to be.

I learned he taught elementary school for 18 years and then retired to become an administrator. I learned he was 5’10” tall and 165 pounds, and in good shape — able to ride 100 miles in under five hours. I learned his name was Sylvester, although he told me everyone calls him “Sly,” and that I could too.

I learned Sly is 57 years old — my same age — although I might have guessed it by his whiskers, which looked like shaved coconut on a chocolate cake.

Back and forth we talked for five, maybe 10 miles, his baritone voice rich and earthy, with an American dialect so familiar and musical I pray it never perishes from the earth. When we reached a fork in the road, we said our goodbyes. Sly turned left, and I turned right.

I may never see him again, but for that one stretch of road, on a bright, cold winter’s day, I felt like I had been dipped in warm, melted chocolate.

God bless you, Sly, fine sir. I pray your journey is a good one, that your days will be many, and filled with too much cheesecake.

Black and Blues!

I'm not sure why African-Americans are so much on my heart and mind. If there is a God, maybe she put those feelings there, because I notice many of my writings are about them. In Richmond, where I lived for 30 years before leaving the US, some 50% of the urban population is black, and yet there was this sad wall between the races. Conversations like the one I had with Sly were rare, making them precious. I long for more fellowship like that, but I found it difficult to climb over the wall, and even harder now that I live O-US (Outside the United States).

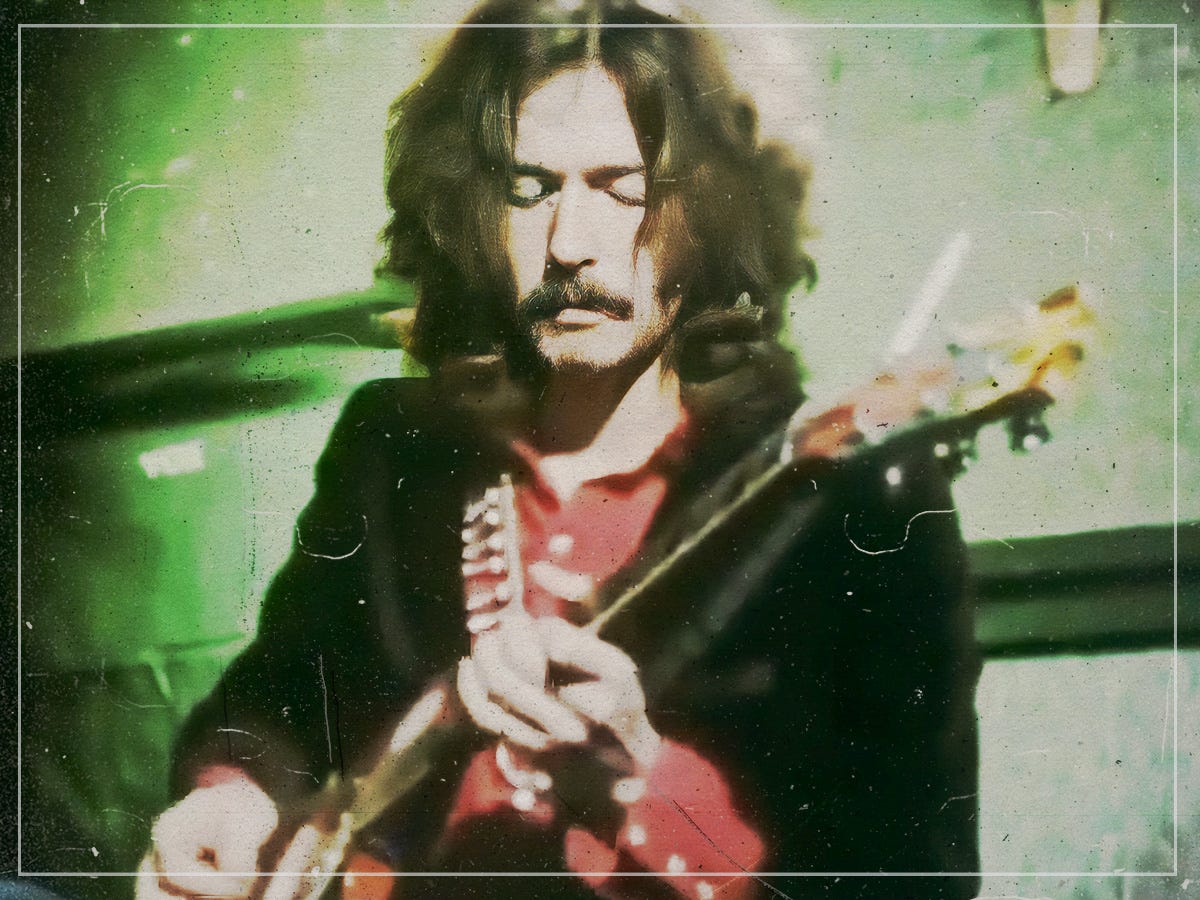

The best I can do, and what I saw myself doing in my podcast, is celebrating all the warmth, color, joy, and richness I believe African-Americans bring to the world. By doing so, I believe I am following the good example of the young, British musicians of the late 50s and early 60s, white cats like Eric Clapton, Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones, Jeff Beck of the Yardbirds, and John Mayall of the Blues Breakers, just to name a few.

These young guys “discovered” the great American blues musicians of that era, older guys like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, and brought them to the attention of an American public largely ignorant of American Blues music, Mr. Presley excepted (Elvis was totally into the Blues). At that time, most young Americans were listening to Leslie Gore (see definition of hell above).

To prove what I’m saying, listen to the classic blues song “Spoonful,” written by African-American Willie Dixon and first recorded in 1960 by Howlin’ Wolf. Then listen to the English supergroup's 1966 version, featuring Eric Clapton’s searing guitar work and Jack Bruce’s powerful vocals. Both versions are so good, but I can understand how and why the young Brits were drawn to the original — “a stark and haunting work.”

That's a Wrap!

I'll have more to say about the many valuable contributions of African-Americans in the coming weeks, but for now, I must wrap up. Fabi and I have a plane to catch... for Scotland! For the next ten days, it’ll be kilts, bagpipes, haggis, and whiskey, or whisky (without the “e”), as the Scots say.

I'll see you on the road!

You still ride a bike? I do and plan a summer vacation in Flagstaff camping and mountain biking and hiking trails. Use it or lose it! Enjoy your trip to Scotland with Fabi.

Thanks for sharing this. The current term in use is AAVE (African-American Vernacular English). I was taught the term BVE (Black Vernacular English) when I was in college in the 90s taking a linguistics course (for fun, as an elective!).